- Home

- Michael Buble

Onstage Offstage Page 2

Onstage Offstage Read online

Page 2

What can I say? I liked to stir things up. It took music to focus me.

The nice thing is that I’m still close to many of the kids from back then. I’m still close to my friend Carsten, who grew up on my street. I have a photo of him and me when we’re five years old, and we’re holding my new baby sister Crystal, who’d just come home from the hospital. Our street was filled with kids, and their parents were so much a part of our lives we’d refer to them as ‘Aunt this’ or ‘Uncle that’. We grew up slow — we had a proper childhood filled with road hockey, gunfights, kick the can, chasing ice-cream trucks and building tree forts. We hung out at each other’s houses, a whole group of kids all roughly the same age. I remember I had a crush on Dana Dong. My first kiss was with a girl named Jennifer Kiss, appropriately enough. She was my friend and she offered to teach me how to kiss. I had a secret crush on her so I was thrilled. But after we’d kissed, she said it’d felt like she was kissing her brother, which so destroyed me that I remember those words to this day.

When I was between eleven and fourteen years old, I wanted to be an actor, so I pushed my parents to take me to auditions for movie parts. I did a lot of community theatre outside high school. Although I suffered from stage fright, I put myself through those intensely nerve-racking auditions. But once I’d discovered the force that is Harry Connick Jr, I knew I wanted to be a singer.

Musically, Bing Crosby’s Merry Christmas album had an enormous impact on me. It is the quintessential record. I hope to achieve a fraction of that classic sound with my own Christmas album one day. As a kid, I sang every one of those goddamn songs on that Crosby record. I was singing ‘Mele Kalikimaka’ come July. The arrangements are gorgeous and swinging, and Crosby’s voice is beautiful. I just fell in love with it immediately. I loved Christmas because of the emotional attachment it had for me, and now there are memories of family and good times. For me, it was sheer perfection for Crosby to mix that feeling with the beautiful melodies and instrumentation.

Let’s face it, I was a weird kid. What other kid would find an old Christmas record so exciting?

I knew I could sing. I used to sing a lot with my buddies. My friend Brad would say, ‘You’re singing with your fake voice,’ because I’d use vibrato. They’d say, ‘Shut up, Bublé.’

But then, of course, I found Harry Connick Jr. I can’t remember where I heard him first, but I knew I’d fallen in love with the song ‘It Had to Be You’. I really enjoyed his voice and realized I could emulate him. I started doing Harry Connick Jr impersonations at school, and I’d make everybody laugh. I also did a mean Christian Slater impersonation. More importantly, Connick taught me that I could sing with my own style. I didn’t have to use vibrato or funny voices; instead, I could sing with authority, like a pro. It made me realize I was more of a singer than an actor, and that I wasn’t just any kind of singer. My voice doesn’t sound like every voice. If I wanted to sing hard rock, for example, I couldn’t, because my voice hasn’t got that tone. I would sound like a crooner singing hard rock.

At fourteen, I had another revelation. I was walking through a shopping mall with a friend. We spotted a cute girl, so my friend walked up to her and told her I thought she was cute. And then he said, ‘Michael, sing for her.’ So I sang. And I got her number and we dated. She was one of the first really cute girls I dated. And I got her through singing. It really hit me that there’s power in that style of singing.

I had a rich fantasy life at this time, too. Every time I heard a song on the radio I fantasized it was me singing it. I’d sing into the mirror, pretending I was playing to a rapturous crowd at Madison Square Garden in New York. I’d watch a movie and fantasize that I was playing the lead role. There was always fantasizing and make-believe. As a teenager, I spent six summers working on my dad’s salmon fishing boat. I’d sit there in the middle of the night on a four-hour wheel shift, listening to Tony Bennett, singing along and pretending I was singing with him. I wrote songs in my head while working on that boat.

My dad’s boat was also the place where I learned to act like a man, not a bratty kid. My dad Lewis taught me that if I acted honourably with people, they would act honourably with me. His crew respected him, and that stuck with me. It was hard work, and we couldn’t wear gloves because they’d get caught in the nets and rip our arms off. We put petroleum jelly on our hands while we slept to keep them from cracking and bleeding. At the end of a gruelling shift, my dad would take out a bottle of whisky and draw the halfway mark with a felt pen. He’d say, ‘You can drink that much, boys, but no more.’ And they’d respectfully drink to the line. He didn’t want a bunch of hung-over guys working for him the next day. But, more importantly, he knew how to manage people without costing them their dignity. Those lessons have stuck with me to this day, especially now that I manage a staff of around a hundred people.

My dad taught me to work hard, so I began doing that at an early age. I started my career by playing any gig offered to me, as many as I possibly could. Nothing was too small. And, of course, I’d play for free, just to have an audience. I’d play to a construction crew during their coffee break if they’d take me. The audiences might not have paid much attention to this baby-faced kid in an ill-fitting suit his grandpa had given him, but I persevered and did my best to win them over. You’d think that a kid with that kind of ambition would be brimming with confidence, but I always suffered with that stage fright.

One time my grandpa heard about a talent show being held at the Big Bamboo, a popular nightclub in Vancouver. ‘You should enter,’ he told me, so I did, using a fake identification card, because I was a little under the legal drinking age of nineteen and wouldn’t have been allowed inside a nightclub. My grandpa helped me practise ‘It Had To Be You’, over and over, and then we went down to the club. When my turn came, I sang my little heart out.

But I also made a total nuisance of myself to the poor woman who was organizing the show, a no-nonsense lady named Beverly Delich. She told me to shut up at least a couple of times. I had it coming. I mean, I was so excited I couldn’t sit still. I kept saying, ‘Is it my turn? Is it my turn?’ And she said, ‘Shut up and sit down.’ She was really tough with me. I ended up winning the thing and, of course, I thought I’d made it. ‘This is it. My first step to fame,’ I said to my naiéve young self.

The next morning, I had a phone call from Beverly. She said, ‘Michael, the good news is, you’re hugely talented. The bad news is, you lied about your age and you’re disqualified from the competition.’ I was so bloody mad I could barely contain myself. But Beverly went on to say that, although I’d lied about my age, she wasn’t going to give up on me. And she didn’t. I heard from her again.

She had another competition for me to enter, specifically for talented youth between thirteen and twenty-one, at an annual fair that’s hugely popular in Vancouver, the Pacific National Exhibition. I was seriously ticked off about losing my prize in the previous contest, and wasn’t ready to listen to any of that, so I just said, ‘Whatever. Goodbye.’ But Beverly called back and talked with my parents. She told them, ‘Your kid is too good not to do this talent contest at the PNE.’

That clinched it. My parents thought I should listen to her, so I did. She introduced me to Ray Carroll, a former member of the 1950s vocal group, the Platters. Ray taught me techniques to manage my stage fright, and other things, like how to hold a microphone properly, how to work with the band, how to do intros, how to get in and out, how to talk with the band while on stage, how to count tempos, all those little things that I had no clue about.

The PNE is located on the east side of Vancouver, and it’s in operation from late summer to early September. It was there, among the rides, the shouting carnies, the prize-winning games, the cotton candy and the dog shows, that I won the Youth Talent Search that summer. It was 1995, and I was twenty years old.

It boosted my confidence tenfold. It made me think that I could have a crack at a professional singing career. I believed I was

on my way, and I hadn’t lied about my age, so the prize was mine.

To top it off, that night I landed my biggest paying gig, at a jazz club called Rossini’s, for around fifty dollars. That was big-time money. Up until then, I’d been getting paid around twenty dollars a performance.

The PNE Youth Talent Search winner got to go to Memphis, Tennessee, to tour Elvis Presley’s Graceland estate, and to compete in another talent contest, the International Youth Talent Search. Beverly would go with me. On the plane, I asked her if she would be my manager. Of course, because I was this brilliant young man, I put it to her like this: ‘You know, Bev, I’m going to be huge here, this is my start. Would you want to be my manager?’

She turned her head and looked at me straight on. ‘No,’ she answered.

I said, ‘But, Bev, I’ll give you fifteen per cent of my earnings.’

And she said, ‘Honey, what is fifteen per cent of nothing?’

I couldn’t argue.

I went to Memphis and performed badly to a crowd of about two thousand people. I came third or fourth – and I was a terrible loser. I was the most ungracious person on stage. When they handed out the award they gave us all these silver plates. In front of everyone, I bent mine. When I went backstage, I kicked over tables, I threw stuff, I went nuts. The kid in me with the bad attitude emerged. I’m so embarrassed to think about what a jerk I was. We flew home.

Later, I called up Bev and had a heart-to-heart. I tried again to convince her to be my manager. I said, ‘Bev, you can’t quit on me if we’re going to do this. You’ve got to promise me you’ll never leave me.’

She said she’d do it. She had faith in me.

Suddenly, I had a manager. All I needed next was a career.

In Limbo in L.A.

Over the next couple of years, with Bev’s help, I began playing around town, landing regular gigs and building a little following. Once I got the regular gigs, I knew how great it could feel to play for a crowd that was there for you, instead of a crowd that was there just to drink. Less than a year after my PNE win, we booked a gig in the bar at one of Vancouver’s fancy old hotels, the Georgia Hotel downtown. I’d play to packed audiences every Saturday night for about eighty dollars. There were big windows that looked on to the street, and passers-by could see me playing with my band — local musicians Bev had helped bring together.

I’d sing classic tunes by Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Tony Bennett, and anything that would lend itself to swing, including my jazzy rendition of the Spider-Man theme song. I’d always loved it, and it was no accident that when I landed a major-label deal many years later, I immediately wanted to record it.

My timing was fortunate. There had been a big swing-music trend a couple of years earlier that was bolstered by the popularity of the 1996 Vince Vaughn movie, Swingers. Young audiences were already acclimatized to swing music and lounge-era jazz tunes, like ‘Mack The Knife’ and ‘Summerwind’. As a consequence, there were other young swing acts in town, although most didn’t follow the genre as purely as I chose to. I was a straight-ahead lounge act, nothing trendy or edgy about me, other than that I was twenty-one years old and attempting to charm my audiences. One of my earliest newspaper items read: ‘He sounds like Harry Connick Jr and resembles Jason Priestley. At 21, Michael Bublé’s dream is to perform at Madison Square Garden . . . For now, he’ll have to content himself with packing them in at the Georgia Street Bar and Grill and living at home with Mom and Dad.’ That blurb would prove prophetic.

I continued to play everywhere for any amount. One time, I played to about two thousand people with a well-known old-time Vancouver act that has been around for seventy years, the Dal Richards Orchestra. Bandleader Dal, who’s in his nineties, is still going strong today.

In 1996, I landed a gig playing a private post-show backstage party for the Three Tenors on New Year’s Eve. They were playing to fifty thousand people. My job was to entertain the tenors while they dined with their families. Nobody could have guessed that, one day, the night’s dinner entertainment would be playing to crowds as big as a Three Tenors’ audience.

I remember I was booked to play for about twenty minutes and one of the tenors’ assistants came over and said they were enjoying what I was doing and I was to continue. He didn’t say it in a nice way. I wasn’t asked. It was an order. However, they paid me more because the gig went on longer.

Luciano Pavarotti, Placido Domingo and José Carreras looked like something in a zoo: they were behind these red ropes eating dinner with their families and people were taking pictures of them.

Just a year later, in the spring of 1997, I played to a sold-out audience at the Michael J. Fox Theatre in Burnaby, which holds about six hundred. It seemed like the entire Italian community had turned out, probably because my grandpa had invited them all. I even had groupies hanging around the front of the stage. It was a total kick. My friend Jack Cullen was in the crowd. He was a legendary old-time radio personality and played my songs on a popular local radio music show called The Owl Prowl. It was my very first radio exposure, and I’ll never forget the thrill of hearing myself coming over the airwaves. It was like a drug.

That summer, a nightclub owner named Vance Campbell gave me a regular gig at a new, Havana-themed supper club called BaBalu. As soon as I performed for him, Vance became a huge supporter. It was a Sunday-night show hosted by a local radio DJ named Jason Manning, who was my age. He and I became fast friends. Manning had an AM radio show that played old jazz classics, including songs off my independently released CD, First Dance, on which I covered songs like ‘I’ll Be Seeing You’ and ‘All Of Me’. I am a total baby- face in the black-and-white close-up shot on the CD cover. I was just a kid. And I was so stoked to be getting radio exposure – even though, looking back, I imagine the number of listeners was minuscule. In those days, I was grateful if even one person bought my CD, which we were selling out of the trunk of my car. I was a hungry, eager kid.

I also played Monday nights at BaBalu, but it was on Sunday nights that my parents and Bev would come out and sit in the front row. The show quickly became a major draw, and I was pulling in around fourteen hundred dollars a night, which was a lot of money at the time. Of course, I had to pay my band out of it, so it didn’t go far.

I also became the ‘go to’ guy for a national TV talk show called The Vicki Gabereau Show. Whenever they had a guest cancel, they’d call me as a replacement and I’d get into my suit and run down to the studio just for the chance to appear on TV. It was at one of these last-second fill-ins that I got to meet jazz singer Diana Krall, who’s also from British Columbia.

Around this time I started doing some musical theatre and making better money. I co-starred in a musical called Red Rock Diner, in which I played a young Elvis Presley. It was during this production that I met my long-time girlfriend, the dancer, singer and actress Debbie Timuss. Debbie and I co-starred in another period musical, Forever Swing, in 1998. In both shows I got to pull out my favourite Elvis Presley moves, which I do to this day. I even had the honour of demonstrating them for Elvis’s ex-wife, Priscilla Presley, backstage at my Los Angeles show in 2010. She was a very sweet and gracious lady, and she didn’t laugh once.

Although I’d garnered some success as a local singer, my promising career felt like it was foundering. Nobody outside downtown Vancouver would have known my name, and even then I was known only to theatre-goers and lovers of lounge music. I was getting impatient to take it to the next level, but I wasn’t sure how.

Forever Swing producer Jeffrey Latimer decided to take the show to Toronto, so Debbie and I went with it. In Toronto, I made decent money doing the musical, but it only lasted a couple of months. Afterwards I picked up some work playing regularly at the local clubs. Mostly, though, I found my career hitting another dead end. I began thinking about a career in broadcast journalism. I liked talking to people, and I had a flair for being on camera. Maybe I could make it work.

Beverly, however, thought I was

being ridiculous. She said, ‘Honey, you’re too good. It’s going to happen, I promise you. It’s impossible for it not to happen. People are going to see you, and they will flock to you.’ She believed in me, even when I was filled with self-doubt. For the first time in my life I really did wonder if I was deluded. It was an extremely dark period, that’s for sure. I took a look around at all the other hungry actors and singers out there who’d never had a chance. Was I one of them? At the back of my mind a little voice was saying, ‘It’s never going to happen, Michael. You might have missed your chance already. You’re going to be a poor nobody.’ I was twenty-four or -five. Today, I think, How silly for a twenty-five-year-old to be feeling washed up. But at that age you don’t feel like a kid. You’re an adult, and you have to figure out a real way to make a living. Mommy and Daddy can’t take care of you. You have to pay your bills and eat.

In those early years I released a couple more independent CDs, including BaBalu in 2001, and Dream in 2002. On BaBalu, I recorded the Spider-Man theme song, which would later be used in the 2004 Sam Raimi movie Spider-Man 2 and also remixed by Junkie XL. I hear those self-made CDs of mine sell pretty well now on eBay. To think that back then I couldn’t give most of them away. Also, I got nominated for a Canadian Genie Award for a song for an Eric McCormack movie, called Here’s to Life. Eric is best known as the lead actor in TV’s hit comedy Will & Grace. He’s a fellow Canadian, and someone I now consider a friend.

By 2000, I’d done some TV and film, including a small role in a comedy- drama called Duets, starring Gwyneth Paltrow, directed by her dad Bruce Paltrow. That was about the most exciting thing that happened in my life at this time. Otherwise my career was in a holding pattern and I was seriously depressed.

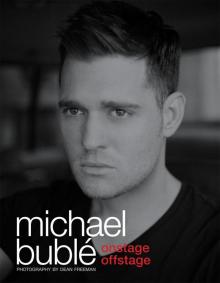

Onstage Offstage

Onstage Offstage