- Home

- Michael Buble

Onstage Offstage

Onstage Offstage Read online

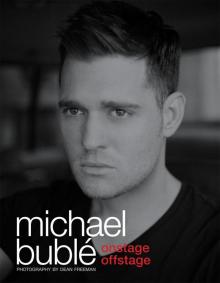

Michael Bublé

Onstage, Offstage

‘In near darkness, I am standing backstage and a sound guy is shoving a microphone pack down the back of my pants. My assistant is straightening my tie, tucking in my shirt. The staircase to the stage is before me. My band is assembled and waiting on that stage, and beyond that are about 30,000 people who’ve paid their hard-earned cash to see me perform. It is in that moment I am enveloped by a strange sense of focus and calm. It may seem counter-intuitive, to be feeling peaceful just before going on stage in front of 30,000 people. But for me it is sheer bliss...’

Contents

Born to Sing

In Limbo in L.A.

Taking Control

Making it Big

Don't Take Away Their Dignity

Crazy in Love

My Life Now

Photographs

Dean Freeman Biography

Thank You

Copyright

Born to Sing

In near darkness, I am standing backstage and a sound guy is shoving a microphone pack down the back of my pants. My assistant is straightening my tie, tucking in my shirt. The staircase to the stage is before me, my band is assembled and waiting on that stage, and beyond that are fifteen thousand or so people who’ve paid their hard-earned cash to see me perform.

In that moment I am enveloped with a strange sense of focus and calm.

It may seem counter-intuitive to feel peaceful just before going onstage in front of fifteen thousand people. But for me, it is sheer bliss.

They tell me I have sold 27 million records worldwide, and I was among the top five biggest grossing North American touring acts of 2010, along with veterans Bon Jovi, Roger Waters, the Dave Matthews Band and the Eagles.

Those numbers are nice because they tell me I’m doing something right. But it’s at that moment when I’m about to climb those stairs and go on to the stage, feeling the audience’s anticipation and my own anxiety that I’ll do a good job for them, that I feel the most gratitude. It’s when all is right in my world because all I ever wanted to be was a performer. I wanted it so badly that, to me, this chaotic, insanely busy and structured life I’m living – flying from country to country, playing one tour date after another, sometimes around 150 shows a year – makes wonderfully perfect sense.

The journey from singing into a hairbrush in my suburban Canadian bedroom to singing onstage at New York’s Madison Square Garden was a much longer one than most people will realize. I’m young, still in my mid-thirties, but I started performing when I was too young to drink and shouldn’t even have been allowed in nightclubs. I was also young and naiéve enough to think that making it was easily within my grasp. I was wrong. I had to work, beg, and charm my way on to that stage, with the help of a group of people who came to believe in me, even when I didn’t totally believe in myself.

It all began when I was a little kid, when I learned my family’s address. My father taught me to sing it, because he knew that by singing it, I’d remember it. I’ll never forget the little tune I composed to sing those four numbers and the name of the quiet street where I grew up in Burnaby, British Columbia. That little song was my first foray into music, and it came to me as naturally as shooting a hockey puck.

My maternal grandfather, Mitch Santaga, was responsible for introducing me to the old American standards, usually sung by Italian immigrants like my own family – crooners like Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. I think you could definitely make the link between Italians and this kind of music. With Italian families, there is genuine warmth and a lot of love, tactile, hands-on love. We love our family, our food and our music.

Grandpa Mitch loved those old singers, and he taught me to love them, too. I spent a lot of time hanging around my grandpa because we’re a family who love each other’s company. Let’s just say that, at Christmas time, nobody’s dreading the holidays. I love Christmas because it is precisely all about family. My family sustains me. I couldn’t have achieved any kind of success without their love and support. They shaped me into the man I am today, and if I should ever lose sight of that, they’d be the first people to kick my butt into shape. That’s important, because I’ve achieved enough success that people aren’t always upfront with me any more. They tend to agree with every idea that comes out of my mouth, and I don’t hear the word ‘no’ so much.

Being famous has the double-pronged reality that everybody will listen to your stories and laugh whether or not they find you funny. That kind of thing can be a hindrance to your growth as an artist. I don’t have to mention the names of talented performers who’ve lost their path in life as they became more famous. We know who they are, and I have a strong suspicion that part of the problem was that people either stopped levelling with them, or they stopped listening. My family, on the other hand, is my trusted judge and jury, and I will listen to them as I have all my life. My mom, Amber, for example, has no problem telling me if I’m being crude and lewd, which isn’t entirely unnatural for me. Anyone who’s caught my show will know about my propensity for the risqué and dark side of comedy. If I take it too far, though, my mom will phone me up. ‘Michael, did you really need to say that?’ she’ll ask, in the disappointed tone that kept me in line as a kid.

When I was growing up, she was the perfect blend: a mother I was afraid of, who was also a great guiding presence for my two sisters and me. It was a healthy fear. And she didn’t cross the line like some parents do and become our best buddy. Who needs another buddy? We needed a mom. She was a disciplinarian. You didn’t mess around. She was a good, fun young mom, but she could put me in my place with one look.

And I wasn’t an easy kid to raise, believe me. One time a reporter asked me what terrible things I’d got up to as a kid. What didn’t I do? I was a jerk. I went through some bad times, especially in my teens. I was fighting a lot. I was really angry. I was insecure and I think I took it out on the people who loved me most, as many of us do. When we’re not feeling great, we hurt the ones we love.

I don’t have kids yet, but I know that I’ll raise them like my parents raised me – by being strict, loving and hopelessly devoted. Kids need boundaries to make them feel safe. But I’m skipping ahead of myself here. Let me tell you more about my upbringing, because it explains everything that I am today, not just professionally but as a person.

My dad worked as a commercial salmon fisherman and my mom stayed at home to raise my younger sisters, Crystal and Brandee, and me. Our house was boisterous and at times loud, compared to my friends’ homes, which might not be too surprising, considering our Italian heritage.

I contributed to the chaos by fulfilling my cliché role as the big brother who tormented his little sisters. To this day, I still call Crystal ‘Joe’ because I caught her kissing a kid named Joey when she was five or six. Oh, that was a beautiful moment for me because I had new ammunition. ‘Joey, Joey, Joey,’ I’d taunt her. She’d go crazy.

When my parents would leave me to babysit, I’d tell Crystal or Brandee to put on my big padded hockey pants and play goalie so I could practise shooting pucks off them. I was obsessed with hockey, my second greatest passion next to music. Being the human target could be a terrifying game for a small child, but I was an evil big brother. If they didn’t obey me, I’d threaten to take them downstairs to the basement and put their little hands on the hot- water pipes. Then if they put on the hockey pants, which were way too big for them, I’d hold them down on the floor until they got claustrophobic and screamed their heads off. I’d sing, ‘Sleepy time, sleepy time, it’s sleepy time in the city.’ I drove them crazy.

Of course, once I got old enough to like girls, I’d hang out with my sisters so I could talk to their friends. They both

had gorgeous girlfriends who wanted nothing to do with a chunky fourteen-year-old nerd.

I had the typical boy’s bedroom, with a Spider-Man poster and tons of Star Wars toys and decorations, like a Darth Vader light switch. I can’t tell you how many times I sat at my desk at school and concentrated as hard as I possibly could, trying to move the pencil using ‘the Force’. It never worked. Even today, in interviews, I’ll often sneak a Star Wars reference into a quote, usually unbeknown to the reporters. When my bedroom was moved to the basement, my interest shifted from Star Wars to girlie magazines, which I kept in a secret panel in the ceiling.

A huge part of my childhood was devoted to my grandparents. They played as big a role in my life as my mother and father, which is fairly typical of Italian immigrant families. My grandparents are second-generation Italians, descending on my mother’s side from a town outside Pescara, on the east coast of Italy. My grandpa Mitch Santaga’s family came to work in the mines in Alberta, where he grew up as a farm boy in a tiny town called Saunders. My dad’s father Frank was born in Vancouver, and his side of the family is from Dalmatia, originally Italian territory that became part of Yugoslavia after the Second World War. On that side of the family, some say we’re Yugoslavian, others that we’re Italian. Both my grandmothers are of Italian descent as well, but were born in Vancouver.

As for speaking Italian, I know some words and phrases, but I’m not fluent. My grandparents, as second-generation Italians, are more Italian than the Italians in Italy. Because they left the old country so long ago, they have preserved the old ways and traditions, and passed them down to us. That’s why we share a love of music, food and family.

I was close to both my grandpas, but they couldn’t have been more different. When I was little and too young to get a job, I’d spend every day of my summer holidays with my grandpa Mitch. I’d go to his house and listen to old records on his 1970s-era RCA console, lying on the green carpet in his living room. He’d play Vaughn Monroe’s version of ‘(Ghost) Riders In The Sky’, which would send shivers down my spine: it’s a song about steel-hoofed cattle being chased across the sky by the spirits of cowboys damned to hell.

It was during those days and nights at my grandpa’s house that my creative imagination developed. We’d sleep out under the stars on his back deck. He’d tell me the bears were going to get me and really freak me out. I was terrified in the way that little boys love to be terrified. He’d also pretend he could see Indian smoke signals in the distance. We were like cowboys on the range, lying there in our sleeping bags. I loved it.

Grandpa Mitch is a lovable, warm grandpa. Grandpa Frank, who died about a decade ago, was a lovable but irascible character, nicknamed ‘the General’. He worked his whole life as captain of a fishing boat but never learned to swim. In summer, he’d walk around in his shorts, black dress socks up to his knees, with black penny loafers. And he loved Dolly Parton.

One time, he heard that the heavyweight boxing champion George Foreman was in Vancouver, and he was meeting fans. My grandpa admired Foreman. He had heard that Foreman liked salmon a lot so, being a fisherman, he brought along a case of salmon he’d canned himself. He waited for hours in a line-up to meet the legendary fighter, and when he got to the front, he handed him the salmon. Foreman was thrilled. My grandpa explained that he was a fisherman and had heard he liked salmon so had brought him a present. Foreman said something like, ‘Gee, Frank, that’s really sweet of you. Let me sign something for you.’ And my grandpa said, ‘I don’t want your bloody autograph. Why the hell would I want that? Enjoy the salmon.’ With that, he walked off. That was my grandpa Frank.

It was my grandpa Mitch who loved music. He would bring out his Mills Brothers or Brook Benton records, and we’d play them, old vinyl records that would hiss and skip. I sat surrounded by them. When I heard those golden voices, it was like I’d entered a place in time that made more sense to me than any of the contemporary songs my friends were listening to. Sure, I liked the bands that were big when I was a teenager, Guns ’N Roses and Metallica, but I idolized the way the old-time singers could phrase a few poignant words so that they stayed with you long after the music had stopped playing. It was my first understanding of what it meant to make great art, which is to capture a feeling, be it the bitter pain of despair or the sweet bliss of being in love. And they did it with such style, too. This wasn’t sloppy sentimentalism. This was straight-up delivery, and those guys could swing. My grandpa’s passion for that music kick-started my own, and it has bonded us for life. We had our secret fraternity for music nerds, and he loved having a grandson who shared his enjoyment and gobbled up his knowledge of old-time swing music.

To this day, if I go to his house, my grandfather will most likely be sitting cross-legged on the floor of his brick-walled living room, making cassette tapes of his old records. He’ll make tapes of my music now, too. He just loves music. I bought him an iPod and he can’t figure the thing out, but he thinks it’s amazing. I give him credit for instilling in me everything I know and love about music.

Unlike a lot of performers, my career journey has not been solitary. My family has been with me every step of the way. It’s basically been a joint project. For example, when I was making Crazy Love, my fourth album, my grandpa Mitch, grandma Yolanda, mom, dad, two sisters, their husbands and kids hung out for the day and watched me record multiple takes of the ‘Stardust’ track. It was my niece Jade’s birthday, so my mom brought along a big chocolate cake, my grandma Yolanda made her traditional lasagne, and my grandpa brought his home-made wine. Having them there, in Bryan Adams’s Warehouse Studio in Vancouver, was like a typical Sunday in our household, filled with food and banter.

Every so often that day I’d look through the glass and see my grandpa Mitch sitting there, moving his lips to the lyrics he knew so well. ‘Stardust’, recorded by Bing Crosby and everybody else back in the day, is one of his favourite old tunes. The pride on his face was unmistakable. My whole family sat there watching me with that look. It filled me with such love to see them there for me, supporting me with their presence, the way they have all my life. It made me feel like I was at home, not in a recording studio surrounded by techies and equipment. My family has been part of every record I’ve made, every tour I’ve done. My touring crew, which is about seventy strong, is accustomed to seeing them backstage, hanging out. My dad is my financial manager. I’m serious when I say that this is a joint effort. To my family, I’ll always be their little guy, the kid who used to perform for them on the karaoke machine in the living room.

I come from a long line of fishermen, working-class men who worked hard and devoted themselves to family. They’re macho Italian men, and they’re proud of what they’ve earned. But they’re not men who are afraid to show their emotions. As soon as I finished ‘Stardust’, I rushed into the room and grabbed my grandpa’s face between both hands. He put his arm around me and his eyes were moist: ‘This life you have, Michael, it’s crazy. Crazy.’

If I ever need a reminder of what I’ve accomplished, all I have to do is look at my grandpa’s face when I’m singing. The only difference now is that we might not be sitting in his living room listening to the old RCA. Now, we’re just as likely to be in a fancy recording studio or backstage at Madison Square Garden.

My grandpa will sit in the studio for hours while I record, and he’ll fly halfway around the world to watch me perform – even though he’s in his eighties. You’d think a twenty-two-hour flight from Vancouver to Australia might be daunting for a guy of that age, but my grandpa travels like that regularly just to spend time with me.

It thrills me that I can make it happen for him because he wanted to be a singer, too: I’m living our dream. I like to tell audiences how my grandpa Mitch was a plumber who’d give musicians free plumbing service if they’d let me sing with them. While other kids were at the mall, I was in some cheesy hotel lounge singing with guys three times my age. That’s just one small example of the effort my grandpa mad

e on my behalf. He also accompanied me to auditions and talent shows.

Anyone who thinks the journey to showbiz success is hard and arduous is damn right. I was such a cocky kid, so sure of my abilities when I got out of that starting gate. I’d never have known it would take nearly a decade of work and determination – and moments of despair so bad that at times I thought of packing it in.

It’s a cliché, but it holds true: you simply have to pay your dues in this world. Canadian writer Malcolm Gladwell theorizes that it takes 10,000 hours of hard work before anybody – Mozart, the Beatles, Bill Gates – achieves success in their field. I firmly agree. It doesn’t matter how innately talented or gifted you are, you have to work, and you have to work hard, before you earn the right to sit back and say, ‘I made it.’

And, for the record, I’m still not there.

Aside from a happy family, there are other childhood factors that define me now. Burnaby, where I grew up, is a sprawling suburb that butts up against the port city of Vancouver. There is a big Italian community, with lots of Italian restaurants, grocery stores and coffee shops, where old guys sit around and drink coffee for hours. I lived there my whole childhood, and I’m still connected to the place.

I had my demons. My childhood wasn’t all sunshine and lollipops. In high school, I felt like a lot of different people. I wasn’t part of the super-cool popular crowd, and even though I loved sports, I wasn’t a jock. I don’t recall having a steady girlfriend. I wasn’t much of a student, but I was competitive as hell. One time there was this kid in the English class who told me I was stupid and he would do better than me. I made it my mission that year to get an A in English, just so I could beat him.

Meanwhile, I got a D in the easier food-management class because I was so busy chatting up the girls. I don’t want to imply that I was a big hit with them, because I wasn’t. I was a dork who couldn’t hang on to a girlfriend for much longer than a week. I was also an unruly kid who had a knack for getting into trouble. One time I went on a class field trip to a bread factory and stole some bread because I thought it was funny. I was banned from future field trips. My mother was not pleased.

Onstage Offstage

Onstage Offstage